relocating a boyhood

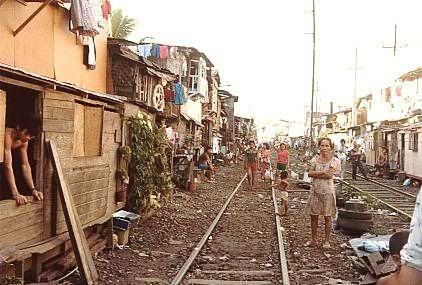

Certainly, evocations of memory have been articulated by way of poetry. But when Andre Breton insists "poetry is a room of marvels,” I am even more compelled to conceive each poem not only as a latitude of metaphors, ideas, and images with a design and a system. In attempting to write a “good” poem about Algeciras Street, I must also carefully attend to the dramatic unfolding of my memories, find ways of interrogating and transfiguring a profound quietude to bring forth what otherwise has evaded consciousness. Consequently, I must afford opportunities for every recollected detail to live dramatically inside the reader. For instance, railroad tracks along my boyhood years must be replicated by attempting to put together raw emotions with the sturdiest of configurations:

Algeciras [2]

Halimuyak ang alikabok at basura

sa paglulunoy ng bawat daliri

paghakot sa kayamanang taglay

ng bote, lata’t mga lumang peryodiko.

Sa Algeciras,

hindi na kailangan ng abaniko

upang magpaspas kung maalinsangan.

Ang mga ugat sa lugar na ito’y nadiinan,

napipi: walang pakiramdam.

But poetry may still shut in the range and scope of such replications. A sequence of intensive states may also be rendered not necessarily by means of a pure assignation of metaphors. This awareness began as I embarked on a teaching career in the university. I was taken in immediately after college because many professors died, retired, or studied overseas. Unfortunately, my moment of glory as a new teacher was heavily muffled by the lukewarm reception of my colleagues. Often some of them reminded me of the provisional nature of my appointment. Others conspired to mark down my teaching evaluation scores. Every semester, I was forced to teach nine classes instead of the usual four. More severely, I did not have an office for months. Then one day the college dean saw my misery—I was sitting down on the floor, correcting test papers along the corridor. When he intervened, my department head was compelled to provide me with a working place. Seeing that no one would take me in as a roommate, the department’s administrative officer immediately secured a utility room vacated by the Psychology Department in the college building’s third floor. While humid and remote from the location of my department, the room protected me from my department’s cruelty for several years.

This turned out to be a glorious blessing. Six rooms away from me, I saw a sign marked “Rene Villanueva” outside an office door. I was such a huge Rene Villanueva fan! It was Vim Nadera, a college friend, who initially invited me to watch several Villanueva plays being staged at downtown Manila universities: May Isang Sundalo, Halik ng Tarantula, Huling Gabi sa Maragondon, Nana, and Kumbersasyon. Unfortunately, I never had opportunities to speak with Villanueva whenever I watched his plays. He was always surrounded by students and teachers from different schools, all wanting to catch a glimpse of him. Since we became colleagues from different departments within the same university, I took the opportunity to quickly jot down Villanueva’s consultation hours then mustered enough confidence to finally meet him upclose. When I finally did, I brought with me personal copies of Mithi 10 (UMPIL, 1985) and May Isang Sundalo (New Day, 1988).

In contrast to many colleagues from my home department, Rene Villanueva turned out to be a nurturing mentor and friend. Almost daily, I had conversations with Villanueva and his roommates Jimmuel Naval and Ramon Jocson. We often talked about books, writers and the day’s political or social issues. Together with his writer-friends Luna Sicat, Romulo Baquiran, Rolando de la Cruz and Maningning Miclat, we frequently walked towards the university food center to have lunch. Several times, he also gave me complimentary tickets to his plays. It was Villanueva who first saw my potential to write poems in English and Filipino. And he often encouraged me to submit manuscripts to Ani, Diyaryo Filipino, Filipino Magazin, The Philippine Collegian, and Diliman Review. It was disheartening to see him leave the academe for Batibot, his ground-breaking TV project for children. But just before leaving, Villanueva pushed me to attend The Silliman and U.P. writers’ workshops. And soon after, Villanueva asked: Why do you, almost exclusively, write poetry? Can’t you write prose?

28th national writers workshop, dumaguete (1989)

(1st row) felino garcia, rex fernandez, miriam coronel ferrer, nenita lachica, cynthia lopez dee, wendell capili and gemino abad; (2nd row, standing) merlie alunan, marjorie evasco, vim nadera, gilbert tan, dm reyes, luna sicat, cesar ruiz aquino, joey baquiran, timothy wells, jovita zarate, an auditing participant, christine godinez ortega, ramon boloron, lakambini sitoy, edith lopez tiempo and ophelia alcantara dimalanta

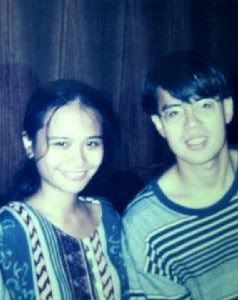

with maningning miclat (1995)

It remains doubtful whether I had actually achieved my projections when I completed a draft of my work-in-progress, courageously entitled “Boyhood.” Still and all, I may have produced a kind of writing that muddles up literary and journalistic conventions to unmask the peculiarities of my life’s dramatic actions, emotions, and feelings.

In writing prose passages about my childhood and early adolescent years, I referred back to my poems as starting points. “Dagta” and “Spilled Ink Elegy,” for example, were attempts to pay tribute to my mother and grandmother. Both women gave up their promising careers (teaching for my mother and dentistry for my grandmother) and became full-time homemakers. In the following lines, I uncovered episodes from my boyhood years where both women unfailingly mopped floors, laundered clothes, scrubbed toilets and kitchen sinks, and sparkled rooms with decorations to warm up their families.

Dagta [3 ]

Pumatak ang sunud-sunod

na dagta ng mangga

sa dalawa kong hita.

Kanina, ito’y pinahiran

ng tapis at ng mga uyayi ni ina.

. . .

Pilit niyang ikinukubli

ang kanyang pagkamuhi

sa mga dagtang dulot

ng aking paglaki. . . .

Spilled Ink Elegy [4]

Black ink spills over grandma’s footprints

deeply, slowly, in pensive streaks

. . . .

When monsters were scary,

grandma cuddled me

against regressive veins.

She caressed the alphabet

with gears of dogcart motion

carving gold from Mother Goose music

in half-ascending tones.

. . . .

Now, I must cry a little,

let scars slip a pungency

back into the old cradle. . . .

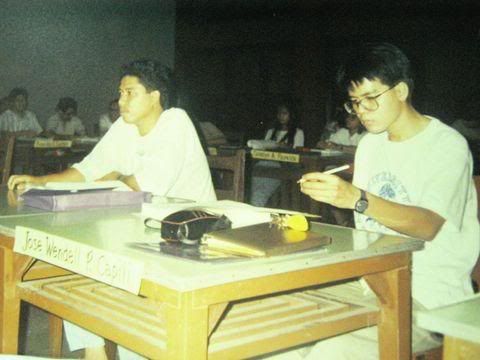

at the 18th u.p. national writers' workshop, diliman (1990)

with roland f. santos

Clearly, I was unable to articulate my emotions and feelings as I had originally envisioned them. Poetry required me to focus simultaneously on rhythm, figures of speech, diction, sentence structure, tone, sound devices, and the use of repetition to create emphasis or unveil mood and tone. In an essay titled “Mothers,” I may have directed my original intentions with more clarity and conviction. Furthermore, my commemorations have also afforded me with opportunities to collectively pay tribute to some of the other women in my formative years.

“My mother was my first teacher. When I was three, she made me recite the ABCs then count from 1 to 100 before our guests. At age five, I loved rummaging through maps and illustrations of Wells’ Outline of History. Upon learning about this particular fascination, my mother persuaded my father to purchase The Reader’s Digest Great World Atlas. The book enthused me to fluently memorize names of countries, capital cities, highest mountains, and other geographical facts.

At UST Elementary School, I had a number of teachers who sustained my interest in learning more about the world outside Carola Street. Miss Mila Bautista was my very first teacher in prep and grade 1. She made me a group leader, often asking me to monitor the cleanliness of our classroom and to keep my classmates’ mouths shut whenever she took a break. When I was stricken with flu, she personally brought me to the university health center and patiently waited for my mother to arrive before returning to my classmates who were all distracted with coloring book exercises. When Ms. Bautista became Mrs. Villarama, I was very sad because I thought she would be resigning. When she returned after giving birth to her first child, my grade 1 class deliriously threw a party for her. The class brought loaves of bread, slices of Kraft cheddar cheese, hotdogs, marshmallows and bottles of Sarsi Cola and Sunta Orange to celebrate her coming back. I would not forget Mrs. Mila-Bautista-Villarama because she saved me from embarrassment many times whenever I couldn’t understand texts the class orally read in unison. She knew there was something wrong with my comprehension skills. But she refused to call me dumb. After each class, she would make me read texts again and again until I finally understood the gist of things. Almost thirty years later, I discovered that I had been afflicted with Attention Deficiency Hyperactivity Disorder since birth. Mrs. Villarama’s creative impulse in sorting out my deficiencies turned out to be what became familiar to us as special education.

“In Grade 1, I also met two other interesting teachers: Mrs. Sylvia Fernandez, who taught me speech communication; and Miss Aida Jurilla, who taught me music.

“Mrs. Fernandez was fully aware of my lapses in speaking and writing. But whenever we had school presentations, she persistently plucked my name either as a lead performer or as part of a chorus. My first public performance was staged at the UST Education Auditorium before a thousand or so people. As her pilot Grade 1 students, we were trained to recite “A Little Boy’s Prayer,” a Vietnam War poem. Some 400 Grade 1 students auditioned for thirty speaking parts. Though I forgot my lines many times, I remained part of the ensemble Mrs. Fernandez had selected to perform onstage. I was among the first ten performers arising on top of a platform to directly face the audience. We were all dolled up in colorful jacket tops and trousers. But minutes before our number, Mrs. Fernandez noticed that I was on the verge of a nervous breakdown, cracking up and shivering in fright. Mrs. Fernandez momentarily pulled me out of the backstage so I can drink a glass of water. Afterwards, she motivated me to close my eyes, pray, and offer my performance to the ones I deeply care for. And she also insisted that throughout the performance, I should imagine that only my family and friends are in the auditorium.

“I still got frightened the very first time I emerged onstage. But Mrs. Fernandez hid behind the curtains to keep me cool, calm, and collected. I kept on whispering to myself “For Grandpa” and “For Mom and Dad” as I uttered the first lines: ‘Now, as I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep. If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take. God bless Mommy, Little Sue, Baby John, and most especially, my Daddy . . .’

“After five minutes, we ended our performance with a bow. And the crowd cheered us on. Mrs. Fernandez embraced each one of us. Then she gave us balloons before we went home.

“When I graduated from Grade 6, Mrs. Fernandez emceed the proceedings held at the UST Gymnasium. Although it was not on the script, Mrs. Fernandez added the words “consistent honor student” as she called my name. Looking back, I always remember Mrs. Fernandez because she made me realize that one speaks in public to communicate an important thought and certainly not to glorify one’s self.

“Miss Aida Jurilla, on the other hand, was my music teacher from Grade 1 to Grade 6. She made quite an impression on me because she looked glamorous without really trying. She nearly resembled the aura of Hollywood stars like Lana Turner and Elizabeth Taylor. She has presence. As she entered each class, she always looked regal with pieces of beads, pearls, and other trinkets adorning her neck. Miss Jurilla taught me how to sing, play the piano, and be aware of rhythm and its nuances. She also introduced Hollywood and Broadway tunes like “My Favorite Things” (from The Sound of Music) and “Sunrise, Sunset” (from Fiddler on the Roof), popular American songs like “On top of Old Smokey, all covered with snow, I lost my true lover, he courted too slow . . . ” and “The Way We Were” as well as Filipino tunes such as “Lulay,” “Pilipinas Kong Mahal,” and “Dahil sa ’yo.” She also taught me how to sing the school anthem in English and Filipino.

“Every time I try to write poetry, I often remember Ms. Jurilla telling my Grade 1 class that music is poetry and poetry is music. Ms. Jurilla has taught me to prioritize the lyric in my writings. I always recognize Ms. Jurilla’s influence in the development of my poetic ear.

“My mother, Mrs. Villarama, Mrs. Fernandez, and Ms. Jurilla were my first teachers. Their collective patience, creative energy, and encouragement pushed me to speak, read, and write.”

Meanwhile, playing with the other kids from Sampaloc and its peripheries (Quiapo, Sta. Cruz and Tondo in Manila as well as Araneta Avenue to Galas in Quezon City) propelled me to write “Sa Pagitan ng Talayan at ni Paul Klee.” In it I endeavored to challenge elitist aspirations being forced on me by formal schooling. As I wrote the poem, I cultivated mixed feelings of revulsion, rage, suspicion, howl, grief, and guilt over the great disparity between cultural refinement (which I have acquired by virtue of my university education) and the numerous patterns of oppression surrounding the community where I lived.

Sa Pagitan ng Talayan at ni Paul Klee [5 ]

Subalit dito, sa dilim na ito,

dalisay ang silahis ng init.

Humahabi ang kalikasan ng magaspang

na gilid ng nakatingarong lata

at papel, kartong nakasabog

para sa kanya na kumukulay

sa bahay ng mga ilusyon

sa mariringal na simborya

at masidhing kinang ng buhay

mismo, na hindi kumukupas.

Ngayon, Klee,

mapipigil mo ba itong dakilang

delubyo ng nakakalunod, nakatangay,

mabangis na sapirang tumatahip

sa mga gusi ng iba’t ibang mga hugis

ng batid mong daigdig?

Ang baog na buhay, Klee,

ay isang walang panahunang

piraso ng sining abstrakto.

Again, I felt the poem had serious chronological and spatial limitations. In “Stratification,” however, I was able to extend the texture of my impressions beyond what I had exemplified in “Sa Pagitan ng Talayan at ni Paul Klee.” Creative nonfiction may have allowed me to uncover the marvels of my melancholy.

“Although Sampaloc is largely composed of people who are not wealthy, a fraction of its population can be considered comfortable. But I did not know anything about stratification until I went to prep school at age five and half. Rodel Pelobello, one of my playmates, often remarked that I had been fortunate to gain admission to UST Elementary School. His father could only afford to send him to Alejandro Albert Elementary School along Dapitan.

“When I turned seven or eight, the distinction between private schools and public schools loomed larger than what I had previously supposed. In the streets of Sampaloc, schools were inherently attached to image and genealogy.

“The more affluent ones were usually sent to Dominican School, a private school located at the corner of Pi y Margal and Governor Forbes (now Arsenio Lacson). It was probably the grade school in our area that charged the most exorbitant school fees. The conventional Catholic families sent their kids to UST or Holy Trinity School in Balic-Balic. The old rich and the financially upcoming ones sent their children to St. Theresa’s College along D. Tuazon, Quezon City, Lourdes School along Retiro, or San Beda College along Mendiola. There were even those who sent their kids to Ateneo in faraway Loyola Heights. Many Chinese Filipinos sent their kids to St. Jude Catholic School (near Malacaňang Palace), Chiang Kai-shek or UNO High School (along Jose Abad Santos), which was owned and operated by the family of film producer Lily Yu Monteverde.

“Those who missed the deadlines set by most private schools ended up in schools with later application deadlines: St. Jude College along Dimasalang or Perpetual Help School along V. Concepcion (between Dapitan and Laong Laan). I also had playmates from schools within the Mendiola-Morayta hubbub: Far Eastern University, University of the East, La Consolacion College, Centro Escolar University, and National University.

“Most of my playmates, however, were educated in public schools: P. Gomez along Andalucia (near Central Market and Zurbaran), Alejandro Albert (surrounded by Dapitan, Casanas, Pi y Margal, and Instruccion streets), Moises Salvador (along Honradez, near G. Tuazon and Governor Forbes), Legarda Elementary School (surrounded by S.H. Loyola, Craig, P. Leoncio, and Lepanto) and Juan Luna Elementary School (along Cataluňa, near Lepanto).

“During my boyhood years, school pants and skirts were usually indicative of wealth, money or power. Private school students blazed city streets daily with their custom-made school uniforms. As a statement of pride, school emblems were frequently highlighted in these uniforms to catch attention. Public school students, on the other hand, felt inferior and resentful because they wore generic khaki pants, faded blue skirts and white cotton shirts. Likewise, those who walked their way to school were envious of those who went to school by car or by school bus.

“Suddenly, we were no longer one happy bunch of kids in the neighborhood. Even Chinese kids stopped playing with us in the streets because their teachers and (some of their) parents called us “Hua Na”—a bunch of barbarians. Several other times, those who were studying in very exclusive schools were indifferent to us because we could not speak their brand of Standard American English. As I got older, my boyhood friends became estranged from everyone else.

“I ended up hanging around with kids from UST. Aside from sharing teachers, UST students routinely got involved with communal exercises such as the annual sports intramurals. Escorted by pompom girls and muses, we wore lustrous uniforms then played basketball, volleyball or football in the athletic field. I was not particularly gifted as an athlete so I often sat in the bench. Overall, the level of competition was pathetic. Even more hideous were the names assigned to each team. In Grade 4, athletic teams were named after birthstones: Pearl (our class team), Turquoise, Ruby, Emerald, Diamond, and so on. In Grade 5, the teams were named after pairs: Beau and Beauty (our team), King and Queen, Lord and Lady, Duke and Duchess, Baron and Baroness. In Grade 6, the teams were named after cars: Ford (our team), Mustang, Volkswagen, Pontiac, and Volvo.

“Alternatively, we were also encouraged to sing and dance during school programs. But Grade 5 was particularly traumatic. My homeroom adviser had initially selected me to recite a Tagalog poem by Lope K. Santos. Minutes before walking onstage, the school authorities bumped me off in favor of a top couturier’s nephew, largely because my presentation was potentially too dense for the school audience. Most importantly, the couturier's nephew was the favorite of all our teachers and his famous designer uncle designed his princely suits and costumes during school presentations. I looked too shabby and dreadful compared to him, whose impersonation of 1970s pop idol Rico J. Puno was truly a class act.

“From the viewpoint of those who were brought up in style and extreme comfort, the little boys and girls who roamed across the streets of Sampaloc were generally lacking in refinement. But even then, there were family members, teachers, and friends who kept Sampaloc kids afloat when things occasionally fell apart. In the long run, schools did not really matter for as long as one gets to acquire the certitude of vision to move on.”

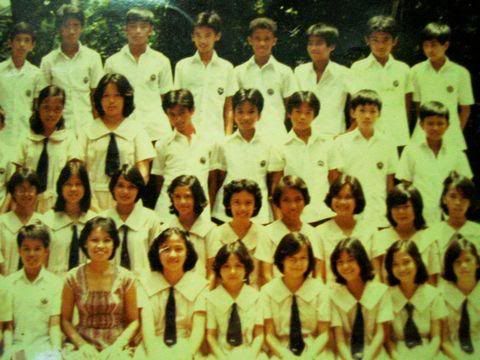

i - st. dionysia

u.s.t. high school, 1979-1980

(1st row) wendell capili, mrs. leticia pacheco (home room adviser), elaine rose teodoro, mary ann juico, elena escarcha, teresa brion, mary ann africa and carla solis; (2nd row) nina marie lopez, geraldine cachola, marie paz salud, portia valle, jesusa posadas, floredliza poquiz, elsa quintana, lourdes cendana and racquel bautista; (3rd row) emilia tiburcio, maribeth miranda, james allan cordon, martin anthony hernandez, raymundo jose, ireneo enrico san pedro and jerome apostol; (4th row) ariel benet, enrico narito, francisco lagonera, elmer reasonda, michael racquel, reginaldo yumul, carlo canares and ariel oliveros.

Sampaloc is also typically associated with floods, garbage, and filthy things that floated all over. In fact, photographs of drenched commuters cruising along Sampaloc’s Espaňa Avenue have appeared quite often in The International Herald Tribune, The New York Times, Mainichi Shimbun and The Sydney Morning Herald. “Ulan,” however, can only afford to make visible my less intricate entanglements with the monsoon season.

Ulan [6]

Malakas ang ulan kahapon.

Dahil dito, nadulas ka

sa taas ng baha

habang tumitirik

ang mga sasakyang

bumubuga

ng sama-samang

usok, alikabok, at grasa.

Tila malalim ang sugat

sa iyong tuhuran.

Pagkatapos ng ilang oras

halos ga-daigdig pa rin

ang iyong mga sigaw

dahil sa sakit-karayom

na humahataw sa iyong balat.

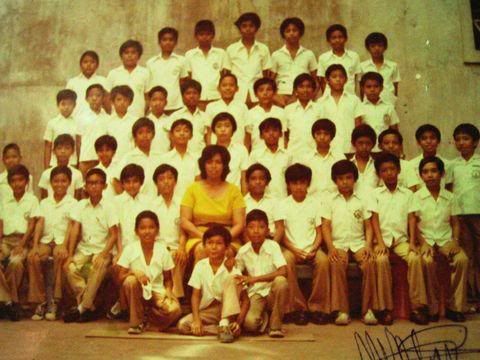

grade III, section b (a.m.)

u.s.t. elementary school, 1975-1976

(1st row) geraldine martinez, rosamond fernando, angelica ilagan, imelda canlas, larrie alinsunurin, carmelinda masagca, cristina pamintuan, roselia bautista, argentina jean dadivas, vidie marie ilagan, cielo gomez and corazon faustino; (2nd row) dolores naniong, cynthia bustamante, maria rowena lucas, mary jane uy, maribeth miranda, maricon angeles, maru ravida, sharon sevilla, ana zecel sanchez, anna loudette santos, josephine sucgang, rowena consumido and antoinette co; (3rd row) ariel monsalud, emmanuel sunga, michael santos, roland garcia, michael gines, rafael rollan, jonathan alegre, jorge gicale, fabian gappi jr., pioquinto diokno, rodolfo soriano, rommel bondoc and manuel sobrevega (4th row) rosauro villamater, tito sadio, nicolas acal, wendell capili, henry yadao, victor paul veloso, orlando macalalad, emmanuel salazar, michael racquel, michelangelo quijano, arnel ricaforte, rogel manalo, elmer arellano and filebon tacardon.

On the other hand, “Floods” enabled me to describe and reflect on what can easily be rendered forgettable. Not even the most enthralling experience in the world can ever make me forget the murkiness of my Sampaloc past. After all, there are lessons to be learned when one gets inundated in a flood.

“Sampaloc is usually infested with floods from June to October. It is a puzzle why residents have constantly allowed themselves to be splashed and squeezed in Sampaloc during the rainy season.

“I take pleasure residing in Sampaloc because I have many family members, friends, and acquaintances all over the district. But there are occasions where floods can be very annoying.

“When I was in Grade 3, I tried to go to school alone in spite of the heavy rains. There were no radio or TV announcements that classes had been suspended. I didn’t want to miss school; I wanted to get a star for perfect attendance by the end of the school year. With my parents fast asleep, I was convinced that I could go to school alone. Quietly, I sneaked out of our house and waded through the waters of Carola Street.

“Upon reaching the corner of Carola and Dapitan, beside the old house of Aling Nita (co-owner of Josephine’s, a popular seafood restaurant chain), I suddenly slipped into a manhole, then nearly got siphoned into its hollow. Fortunately, I managed to gather enough strength to get myself out of danger. Back home, I quickly poured buckets of tap water all over my body then splashed it with Family Rubbing Alcohol. Suddenly, I felt clean and spotless. As I treaded softly back to my room, l vowed never again to aim for a perfect attendance star in school.

“During successive overflows, a number of students from UST, Ramon Magsaysay, St. Jude’s, Perpetual Help, Holy Trinity, and Esteban Abada high schools began to appear in unfashionably gigantic, knee-high black rubber boots. As I was growing up, it became a necessity for me to exhibit these boots as my rain shield and paraphernalia.”

For the reason that school has taught me to be more conscious of associations between signifiers and the signified, it became even more excruciating to remember, reconstruct, and textualize the past. When I wrote poems, I had to frequently note down the indeterminate and playful aspects of language and the tendency to slip constantly from denotation to connotation then back. I had these in mind when I made “Demolisyon.”

Demolisyon [7]

Pagkatapos ng palabas

bagong bihis ang dating putikan

sa pahayagan.

Tuwing sasapit ang halalan

naninibugho kaming mag-anak

dighay ang ga-lungsod na katapangan

sa aming paghahanap

ng isang bagong tirahan.

Consequences, inferences, and postscripts to these issues were hopefully extended in “Dapitan.” By journeying over Dapitan Street, I was able to bring in more details about a geography that dominated my boyhood years. Other than inflating further my disenchantment, readers may also find amusement in recognizing familiar names and spaces as they hit the road where individuals of lesser importance are normally seen passing through.

“I spent my boyhood years playing with children whose families lived around the University of Santo Tomas (UST), in Sampaloc, Manila. Throughout the late 1960s and the 1970s, my playground was Dapitan, a two-way street where jeepneys and calesas moved freely. It was a magical place where I played hide-and-seek with children from the perpendicular streets. And even then, Dapitan was a tributary of stores and dormitories catering mostly to UST students and teachers.

grade v, section d (p.m.)

u.s.t. elementary school, 1978-1979

(1st row) rommel bondoc, homero angelo domingo and amelito tan; (2nd row) bino realuyo, eduardo esquivias, fabian gappi jr., romeo manego, enriquito aguas, mrs. elizabeth duff-mendoza (home room adviser), pioquinto diokno, lyndon lacanienta, richard dyogi, elmer arellano and jose cumento; (3rd row) norbert basa, nathaniel delgado, roberto fernandez, jonathan alegre, danilo dobles, ranel concepcion, eric paul de la vega, ariel oliveros, felixberto garcia, david dacumos, noel siongco and raymund serafico; (4th row) ulysses sta. rosa, ernesto torres, petronilo manalo, cielito candido, bernarlito fajardo, alfredo buyser, daniel gutierrez, riley joy sison, oscar sagalonggos jr. and wendell capili; (5th row) melchizedek manalo, raymond ignacio, joseph mendoza, oscar nanquil, nicandro aure, norman de los santos and gerard flynn franco.

“I have very little recent memory of Sampaloc because I lived overseas. When I returned to the country, I could not find time to revisit Sampaloc. My family moved to a dream house overlooking the city. Elsewhere, matters that compelled immediate attention kept me busy.

When I turned sixteen, I became a resident of an exclusive, Catholic-run student residence hall in Quezon City. I was a devoted member of my church but temporarily found solace in the spiritual organization running the hall. I got good grades in school even when I was squeezing in—before and after my classes—prayers, Bible classes, spiritual readings, and visits to poor communities. Hastily, I accepted an invitation to surrender my life to the organization. But, as it turned out, residents at the hall were mostly students and professionals from upper-class families. Inside the organization, I was a misfit. I was often ridiculed for my plebeian ways, “kasi, galing Sampaloc!”

Hometown [8]

I keep from my children

the dispossession

of a family name

story books

nomads heap on

this antinomy.

I must leave this place

with a fishing pole

tucked under my sleeves

to consume the edge

of my private fears

leaping through

each headwater.

I have decided to cross genres from poetry to creative nonfiction precisely because I want to construct narratives using scenes, dialogue, detailed descriptions, and other techniques drawn from politics, kinship, religion, economics, history, sociology, and the other disciplines. I want to put together research, exposition, prose, a strong emphasis on ideas instead of language vis-à-vis the feel of a literary voice, the elements of narration, characterization, instinct, a strong sense of place where facts come alive and a strong, personal engagement with my chosen subjects. Through each effort, I am bewildered whenever elevations of space, time, and causation are consequentially aligned and transcended.

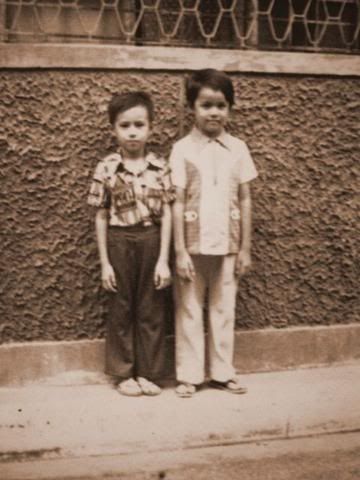

with my brother john, along carola street (1972)

“I used to be ashamed letting people know that I was born and raised in Sampaloc.

“After all, many Sampaloc residents have been unable to seize opportunities to study in elite schools and realize upward social mobility. Around Balic-Balic, for instance, one can easily locate a presence of kanto boys in neighborhood sari-sari stores drinking Tanduay Rhum and Ginebra San Miguel from sunrise to sundown. Every alley in Sampaloc is a playground. There are gay beauty pageants in city streets during weekends. Basketball leagues dominate other streets. Everywhere in Sampaloc there are denizens who cannot speak English properly, who slouch too much, who possess dark and skinny bodies raging with pimples. In enclaves of the rich and famous, they are often ridiculed as “the ones who stink and sweat too much,” “jologs” or “the great unwashed.”

“But I live in Sampaloc, within the proximity of its ghettoes surrounding railroad tracks and alleys, rat-infested dormitories, flooded streets in the monsoon season, and open manholes. Certainly, it is one of Manila’s backwater districts. Outsiders are bewildered. In spite of experiencing varying levels of discomfort, Sampaloc residents have been determined to continuously subsist in the neighborhood.

“The University Belt area is undoubtedly Sampaloc’s nerve center. Here, students from all over the country come to pursue life-long dreams of obtaining diplomas from a Manila university. These schools and universities are: the University of Santo Tomas along Espaňa; Far Eastern University along Morayta; University of the East (UE) and San Sebastian College along Azcarraga (now Claro M. Recto); and Centro Escolar University, La Consolacion College, College of the Holy Spirit, and San Beda College along Mendiola. Conveniently squeezed in between are Perpetual Help College near Dapitan; Family Clinic School near San Lazaro Hippodrome; St. Jude College near Dimasalang; Mary Chiles Hospital School behind UE, and scores of review schools specializing in board examinations. These schools and universities sustain Sampaloc. Should these institutions be relocated, Sampaloc will consequently lose its grip on Manila’s cityscape. This is very apparent during summer vacations, semestral breaks, and Christmas holidays—the usually congested streets of Sampaloc become free of traffic.

“These days, Sampaloc has a newer point of convergence. Along Dos Castillas, between Dimasalang and Dapitan streets, an area collectively known as “Dangwa” (after the Baguio-bound bus liner) emerges suddenly as a flea market for fresh flowers from the Cordillera region.

“Dangwa” may soon become a terminal exclusively for passenger buses bound for Ilocandia and Cagayan Valley provinces. Nevertheless, cargo buses from Baguio and other locations arrive every morning to deliver fresh begonias, carnations, violets, tulips (“fresh from Holland!”), lilies, marigolds, blue bells, dahlias, periwinkles, foxgloves, celandines, hibiscuses, lilacs, and variations of the other types. Rows of dormitory houses have been altered severely to serve as flower shops. And during the week leading to All Soul’s Day, the entire area becomes a mixture of flower freaks from all over.

“Sampaloc is densely populated twenty-four hours a day. There are billiard halls, computer rental shops, and areas for computer games for children and young adults. There are food stalls, beauty parlors, basketball courts, and photocopying shops in every street corner. Cars, tricycles, and jeepneys are frequently double-parked in its streets.

“Then and now, Sampaloc continues to disarrange my boundaries of lies and truths. When I lived in dormitories near UP and Ateneo, I often stated that I was born and raised near Sta. Mesa Heights and Welcome Rotunda, never quite admitting that my family had actually lived farther. Meanwhile, scores of Sampaloc houses in their art nouveau and art deco splendor have been demolished. Prefabricated condos have sprouted hastily to meet the housing needs of numerous board exam reviewees, teachers, students, and medical practitioners.

“Sampaloc is an aftertaste that lingers. It continues to burst within its own kind of blooming. My birthplace does not merely lie outside the fringes of Shangri-La, Rockwell, Eastwood, Greenbelt, Alabang, and similar enclaves for the high and mighty. Sampaloc is outside the center and radically striates it. Sampaloc will never cease to unravel subjectivities, pleasures, relationships, and intensities.”

Sampaloc is truly an outflow of continuousness. Writing “Relocating a Boyhood” has enabled me to rearrange intimate, personal, even local pasts outside of Sampaloc’s “official” public histories in the late 1960s and the 1970s. My personal convictions have become engendered creatively between my roots and its intricate gasps and silences.

Relocating a boyhood may certainly transform the lyric of loss into a recovery of one’s identity and subsequent will to come to terms with the jaggedness of everyday breathing.

_____________

Notes

[1]. A version of this work was presented in The 1st Kamustahan: (University of the Philippines National Writers’ Workshop Alumni) Conference sometime in October 2003 in Tagaytay City. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the UP for the writing grant that enabled me to write it. A revised version of this work was published in Philippine Studies Volume 53 Nos 2 & 3 (Soledad Reyes, issue editor). Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2005: 272-289.

[2.] This poem and the subsequent poems cited in this work have all been published in my first book, A Madness of Birds. Ibid., “Algeciras,” p.67. And for a full rendition of the other poems, see Wendell P. Capili, A Madness of Birds (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1998).

[3.] Ibid., p. 69.

[4.] Ibid., p. 49.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home